In my work as a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse, I see first-hand the many pressures a young carer can face.

It’s important to recognise that ‘young carer’ is an umbrella term covering so many different circumstances. No two young carers will be going through the exact same journey. And the breadth of responsibilities can vary greatly. Many also may not recognise themselves as young carers – or they may not want to. This is especially true for children and adolescents, who so often just want to blend in with their friends and school peers.

As with so many aspects of dementia, it’s not black and white. And there’s no step-by-step guidebook to help you along the way.

Changing family dynamics

All of the young carers I support have a parent living with young onset dementia, where symptoms develop before the age of 65.

Whatever the size or makeup of your family, if one of your parents has young onset dementia, the whole family dynamic changes. In many cases, one parent is thrust into a caring role while trying to work and bring in an income, navigate a complex healthcare system, and be a parent!

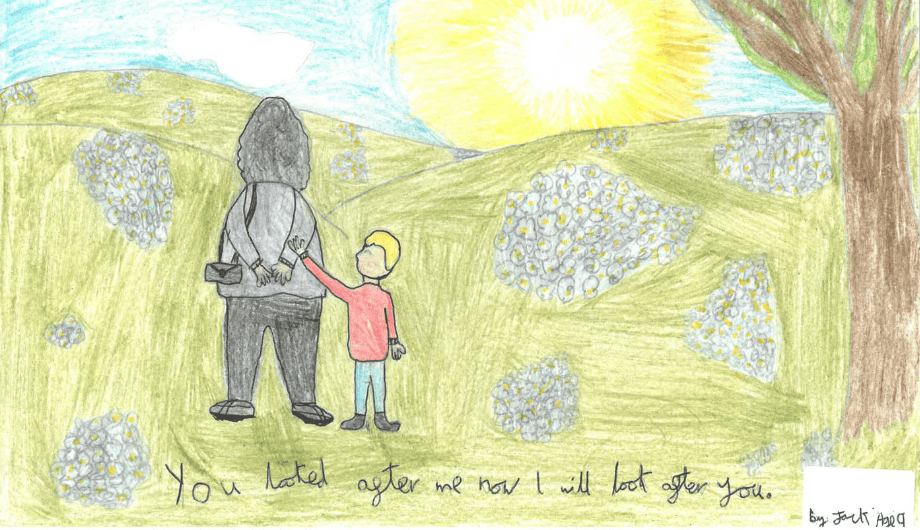

Children who are used to being cared for by their parent may now be asked to care for them instead. Even if a young person is not the primary carer for their mum or dad, it’s likely the diagnosis will mean they’re doing an extra share of the chores or taking care of siblings.

Internalising pressure

One thing I’ve learnt from supporting families affected by dementia is that young people can internalise an awful lot.

When a parent or guardian is living with young onset dementia, it can be hard enough for young people to understand what’s going on at home themselves, let alone feel comfortable sharing the experience with others. They may be anxious about telling friends about the situation at home for fear of being treated differently.

They may also see the stress one parent is going through caring for the other, and not want to draw attention to their own struggles.

Embarrassment, guilt and rolling grief

Young people can feel a lot of embarrassment about the unpredictable nature of someone at home living with dementia. They might ask repetitive questions, use inappropriate language, behave erratically or need help with everyday tasks like eating. For young carers, this may result in social isolation and not wanting to invite friends over. Then there’s the financial pressure that can mean not being able to go on school trips or go on holidays ‘like other families’.

Embarrassment can also give rise to guilt. Young people may feel embarrassed about the reality of their home life, but then feel guilty about being embarrassed about someone they love. It really is a double-edged sword.

So much of dementia is about grief and loss. We often talk about a rolling bereavement, because you’re losing aspects of the person with dementia bit by bit. And then just when you come to accept a new reality, it changes again. It’s a really difficult process when you’re grieving someone who is still alive, and it can be especially hard for children. The anxiety about the future and what may happen to their mum or dad can lead to extreme emotions.

In the families I support, I talk to children about their feelings of loss. It’s not an easy conversation to have. A lot of people don’t want to have these discussions with young people because they don’t want to add to their distress. But avoiding these conversations can create a barrier to accessing timely support before their distress grows.

In my experience, hiding things from children in order to protect them often backfires. This is because when things change suddenly, or the person with dementia deteriorates rapidly, it’s much more of a shock. This can lead to even greater levels of anxiety.

Open dialogue with schools

I always encourage the parents I work with to have an open dialogue with their children’s schools. The two environments young people spend the most time in are school and home. It’s important there is two-way communication between them.

Obviously circumstances differ depending on the age of the young person. A primary school pupil is going to need different support to a teenager at secondary school. But my advice is to parents is this: after a diagnosis, don’t wait to tell the school. Start the dialogue early.

Pastoral support services vary between schools, but it’s important to find out what’s offered. Admiral Nurses like me can help families navigate these conversations.

Navigating life transitions

Life may be hugely disrupted by dementia, but it doesn’t stop it. Transitions are still occurring – whether they are between primary and secondary school, secondary school and university, entering the workforce, or leaving home.

I’ve worked with a number of young people who have left home to go to university, only to drop out due to the pressures and stresses of being away from home where a parent is living with dementia. There can be a lot of guilt about leaving the responsibility of care to other members of the family. Moving away can feel like they are letting loved ones down.

But transitions are a part of life and growing up. And it is possible to navigate them with appropriate support.

Unfortunately, many young carers don’t get support because they don’t know where to turn. No young carer should have to do this on their own – but so many feel like they do.

Admiral Nurses like me are here to help. Please call Dementia UK’s Helpline to speak to a specialist nurse who can provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia, free and in confidence.