Young onset dementia

Information and resources about young onset dementia, where symptoms develop before the age of 65.

Will’s mum had young onset behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. He shares the devastating impact it had on him and his family.

In October 2016, my mum was cruelly taken from us after a long and destructive battle with young onset behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). She was 58. I am writing in the hope that my experiences may help people understand more about this horrible condition and help anyone who may be going through the same with a friend or loved one. Here is my story.

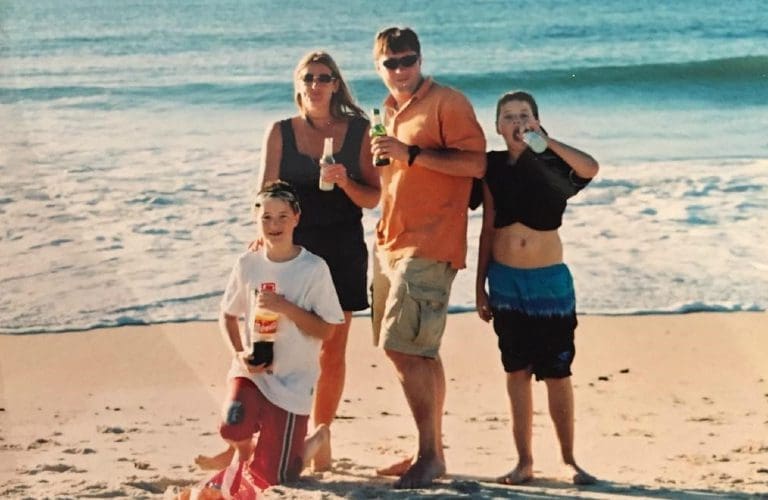

I was born into a loving and happy family. My mum and dad, Liza and Phil, were big parts of the village community whether it was putting on wine tastings, helping out at the church or organising the local kids cricket coaching. In amongst all this they still found plenty of time to raise me and my twin brother Ed. We spent our childhood going from cricket practice to football matches, holidays on the beach to weeks in the Alps. Life was bliss. At the age of 13, we both got academic scholarships to Shrewsbury School. It was while we were boarding there that things started to change with mum.

One of the curiosities with this condition is that the more things progressed, the further back we looked and pondered how the signs had been there for a while before the diagnosis. I’ll never forget the day back in 2011 when we were home for half term. Mum was out so it was just us and dad having a boys evening in and that’s when he told us that she had been diagnosed with bvFTD. It took a lot of time to process. How could she have dementia, that’s a disease for the elderly? Where do we go from here? What could have caused it?

However, after the dust had settled, I then started to realise that this explained a lot of what had been happening. For the previous year or two there had been countless instances where mum had maybe seemed different, not quite herself. She was always quite an eccentric woman, but this was different. Her and dad would argue way more than they used to and we as kids couldn’t fathom why.

Mum would say things which were beyond the normal parental embarrassment, they were just wholly inappropriate. Some put it down to menopause, some even thought she had turned to drink. Dad and mum’s brother, Jamie, grew evermore concerned and asked her to go to the doctors. She went but at that point was still very much lucid and explained herself, so the doctor too thought it was nothing more than menopause. It was only when dad and Jamie stepped in and accompanied her to the doctors, they found out the disturbing truth.

My dad once described the condition as a form of ‘gradual bereavement’ and I believe this summarises it perfectly. As it progressed, my mum would continue to lose more and more of herself. Fairly early on she had her driving licence taken away, she lost the ability to cook and look after herself. The choir which she loved reached the point where they couldn’t accommodate her anymore – they were very kind and understanding about it, I cannot speak highly enough of them.

The thing which shocked me about that was that I was there when she heard the news and she barely batted an eyelid, such is the nature of this condition that she lost all inhibitions and just didn’t understand what was happening.

She became incredibly hostile towards those closest to her, especially dad, and at times it was like trying to control a disobedient child. The more we told her not to do something the more she wanted to do it. As I was away at school / university for the majority of this I would notice the changes every few months when I came back home.

Eventually we needed a live-in carer as dad was still working in London and me and my brother were away at university but even this proved to not be enough. Finally we had to find a care home so she could receive the 24 hour care she needed as well as have a routine which was impossible to provide at home.

Dad found a care home after much searching for one which was age appropriate. The place was just what she needed, brilliant staff, a large garden for her to walk in, a full timetable of activities and only half an hour away from us so we could visit easily. She moved there in early 2014 and whilst it made both her and our lives easier, dementia continued to chip away at her. She eventually lost the ability to walk, her speech disappeared and the occasional grunt would be her only form of communication. She passed away in her bed, surrounded by family on 25th October 2016.

One of the things about dementia and other terminal diseases is that it doesn’t just affect one person, but all those around them. Upon first diagnosis, we felt a whole mixture of emotions. Personally, my initial reaction was shock as I couldn’t believe that it could happen to someone so young.

This was followed by overwhelming sadness upon realising this would inevitably kill her. As things became increasingly difficult at home, tempers became more and more frayed. We never knew what she was going to do next, where she was going to wander off to. As much as we tried to hold it in, sometimes we would shout at her for something she had done but, of course, she just didn’t understand.

A lot of this stress was alleviated once she moved into the home as we no longer had to concern ourselves about her safety or her whereabouts. Around this time, I was in my first year of university and trying to deal with all this on my own. Around my friends I was loud, cheerful and my usual self. However, when I was on my own, I would constantly have these thoughts rushing through my head. I didn’t sleep and I would go out drinking a lot not necessarily always because I wanted to but just because I didn’t want to be alone with my thoughts.

I never spoke to anyone about it and as a result, I failed my end of year exams. I was brought up in front of the progress committee who, after hearing my home situation, allowed me to continue my studies providing I re-took the modules I failed. I then decided I needed to be more open. I signed up for weekly counselling, spoke to my friends / family whenever I had a low moment and generally got my life back on track. I graduated in July 2018, something I previously didn’t think I would ever manage.

The five years between diagnosis and her passing were incredibly difficult and put a huge strain on all of us. I can’t describe how painful it is to watch someone you love fade away like that and I guess the only slight solace we got was that she was completely oblivious to it all. However, after her death things did slowly become easier.

Obviously, it was still sad, although she hadn’t been anything like herself for a while, at least beforehand I could go and physically see her. Now I couldn’t. That being said, it was sort of a form of closure. We could now begin to move on and try and remember the good stuff, rather than the bad. The first anniversary was still a tough day but every year since it has got easier. We can now look back on what we had with her, the kind and loving mum, a friend to all. Everyone has at least one happy memory of her. Everyone has a story. I certainly have plenty.

As I said at the start, I have written this for the purposes of helping people understand the condition and indeed how I coped with it. The one piece of advice I would like people to take away is that if you are going through something similar (or in fact anything difficult) it’s so important that you talk to people whether it be a counsellor, a family member or just a close friend.

My hope is also that people can be made more aware of this condition and the fact that it can strike younger people. This way if someone knows someone who is diagnosed, they’re a little more clued up than I was.

To finish off I want to give a little update on how I am now. It is approaching five years since mum’s passing and thankfully I can report that things are noticeably better. I still have the occasional wobble, a late-night tearful phone call or two from time to time, but all in all I am in a much better place.

It is still not easy. Mum is never far from my thoughts, and I will never completely get over this. The reason why I say this is because I want to reassure anyone who may be in the same situation (or similar) that it is okay to not be okay. People deal with trauma in different ways and there is no roadmap. Whatever you are going through and however hard it is, the most important thing is to talk to someone and let it out.

I am fortunate enough to have a brilliant support circle around me and its imperative that, if you are struggling, you find yours. I don’t know where I’d be right now if I hadn’t done that. Mum was so dedicated to helping people throughout her life. If me writing this can help one person or provide some form of comfort, then at least something good has come out of all of it.

Will, is a 27-year-old languages graduate currently living and working in Barcelona.

Information and resources about young onset dementia, where symptoms develop before the age of 65.

Help us raise vital funds, improve care and support for families facing dementia and spread the word about our specialist dementia nurses.

Sharing your story with Dementia UK can help to inspire and reassure others who may be going through similar things.