Charles and I met at a music summer school in 2003 and had an instant connection. Within a few months, we moved in together and married in 2006.

Music was Charles’s great passion in life. He was an esteemed clarinettist, conductor and composer.

Charles was a beautiful, kind person. Everyone agreed.

Early signs of dementia

I remember the first time I became concerned something wasn’t right. It was August 2016 and Charles was conducting a youth wind orchestra. Before the concert, he took off his linen jacket and put on his conducting jacket. After the concert, he couldn’t remember where he put his linen jacket, and accused me of misplacing it. It was so unlike him.

More signs followed. There was another one-off occasion about 18 months later when Charles forgot how to adjust the heating in our house. Later, he struggled to figure out power sockets. And he’d lose things, even when they were in the room he was standing in.

Charles queried things with the doctors several times over the course of 2019. They would conduct the briefest of memory tests during the GP appointment, which he would pass with flying colours. They surmised that it couldn’t be dementia – after all, Charles had no problems remembering a name and address for five minutes!

It was so frustrating hearing medical professionals rule out dementia based on this test alone. The reality was that they simply didn’t have the necessary training, and therefore didn’t understand dementia and its complexities.

In September 2019, after I pleaded with the GP, they finally referred Charles to the Memory Assessment Service.

Receiving a diagnosis

Charles’s symptoms begun to intensify at night. He’d twitch and flail and fall out of bed. I had to order a crash mat to put on the floor by the bed. I also had to get sensor lights and a door alarm as he’d sometimes walk into the porch, thinking it was the door to the bathroom.

Somehow, Charles had still been able to conduct up until December 2019. But then, during a rehearsal he began to make mistakes, conducting the wrong number of beats in a bar or miscounting the number of bars. He had the insight to realise it was no longer viable for him to conduct and retired after the Christmas concert.

On 14th January 2020, following the results of an MRI scan and a detailed cognitive assessment in November, Charles received a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment.

He cancelled rehearsals for all upcoming chamber music concerts he was to have performed in. As Duke Dobing, a flautist, would later say at Charles’s funeral, “The curtain was coming down on a long and distinguished career.”

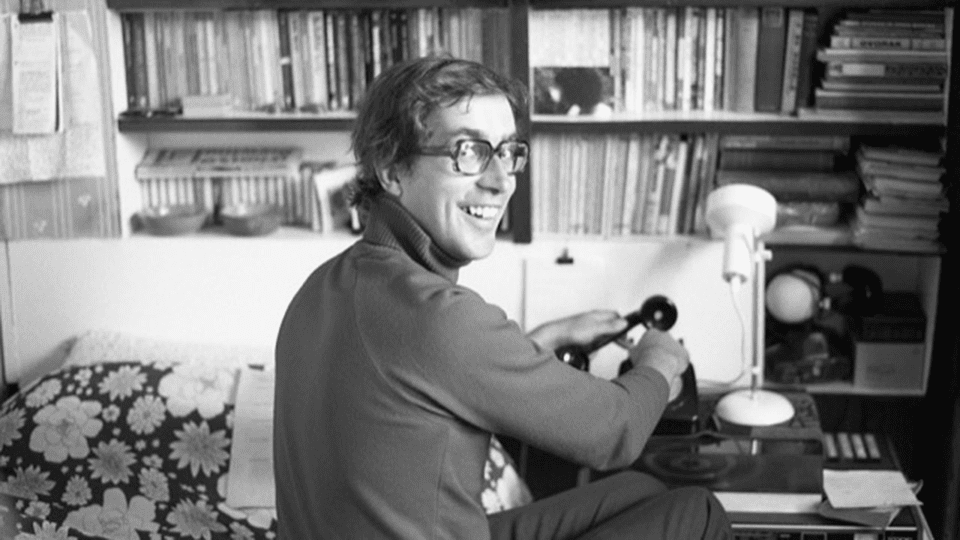

Charles (far right) with his wind quintet in the 1970s

I wanted a proper diagnosis for Charles. But then, a new layer of stress was added. Covid-19 forced the UK into lockdown. Doctors wouldn’t see us. I eventually convinced the local NHS to conduct the psychometric assessment via Microsoft Teams and I shared all the observations I’d written down in the months leading up.

On 17th September 2020, Charles was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

I was forced to give up my job as an academic tutor to care for Charles full-time. From that point on, I was very much living his life rather than my own. But looking back, I would do it all over again.

It sounds strange but the diagnosis was something of a relief, and certainly not a surprise. I had done so much of my own research that I knew what was coming. Charles did too. But I needed support in understanding this specific type of dementia and what to do next. All I received post-diagnosis was a huge package on my doorstep, containing hundreds of pages of documents to read through. I wanted someone to talk to, not a mountain of reading material. But the NHS couldn’t give me that.

Our Admiral Nurse, Rachel

It wasn’t until I spoke with Rachel, a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse specialising in Lewy body dementia, that I finally found someone who understood what we were going through. We had a fortnightly call for the next six months and I can’t tell you how helpful that was. She offered practical support, but just as importantly, she gave me emotional support.

In 2023, three of Charles’s compositions were published. I wanted him to still maintain his identity as a professional musician even if he could no longer perform or conduct. Concerts were held in January and May where Charles could hear his pieces being performed; Rachel attended in May, which meant the world. I’m so glad we did this before he passed.

Despite Rachel’s help, our application for NHS continuing healthcare funding in July 2023 was rejected. They acknowledged that Charles needed full-time care, but stipulated that it was ‘not for medical reasons’.

Charles’s final days

The final 10 weeks of Charles’ life were undoubtedly the hardest. In October, he had a petrifying hallucination that lasted four hours. He was taken into hospital, where he stayed for five weeks, despite the consultant on the ward classing him as ‘medically fit’. I had to argue with them because they refused to acknowledge his delirium and gastrointestinal problems as symptoms of his Lewy body dementia.

After those awful five weeks in hospital, Charles was moved into a nursing home for another awful five weeks, as most of the staff had no understanding of appropriate individualised dementia care.

What I really wanted was to keep Charles at home, where he was happy. I promised him I’d care for him at home and that it was where he’d pass away. But he didn’t, and I feel that I let him down. He only returned home after his death.

Charles died on 1st January 2024, aged 72.

It’s not easy sharing my story, but I tell it to highlight how many gaps there are in dementia support right now. It is so difficult to find appropriate care tailored to the individual. The lack of understanding about Lewy body dementia was infuriating. The battle for any sort of funding, and the subsequent rejections, left me feeling dejected and exhausted.

In Charles’s final days, I logged into Facebook and put out a post saying that he was reaching end of life. Almost immediately, we were bombarded with messages from people not just in the UK, but around the world. Old students, colleagues, friends and family, and everyone in between, spoke of his kindness and how he would be missed. They spoke of how he had always been happy to help them however he could. And they spoke of his smile: a smile that just made you feel better when you saw it. I miss his smile so much.

Rachel Thompson, Consultant Admiral Nurse for Lewy body dementia, is employed by Dementia UK and funded by the Lewy Body Society. The Lewy Body Society also partly funds the support of another Admiral Nurse to the team.

We know that dementia care can be fixed. Join us and urge the new Government to transform dementia care so that everyone affected by dementia gets the specialist support they need. Find out more here.