Amy, Chloe and Rob’s story

Amy shares how she, her younger sister Chloe, and their dad Rob cared for her mum who was diagnosed with young onset frontotemporal dementia, aged 47.

Helen reflects on her dementia journey and grief after husband Clive died from frontotemporal dementia in 1999.

I’m not overly sentimental about dates and anniversaries. But on 29th April in 2024, it marked 25 years since I lost my husband, Clive.

The thing about grief is, it never goes away. You just learn to live with it.

Clive was 40 when he began to struggle with reading and writing. He started making frequent spelling mistakes – this from a man who had consistently (and annoyingly) always beaten me at Scrabble!

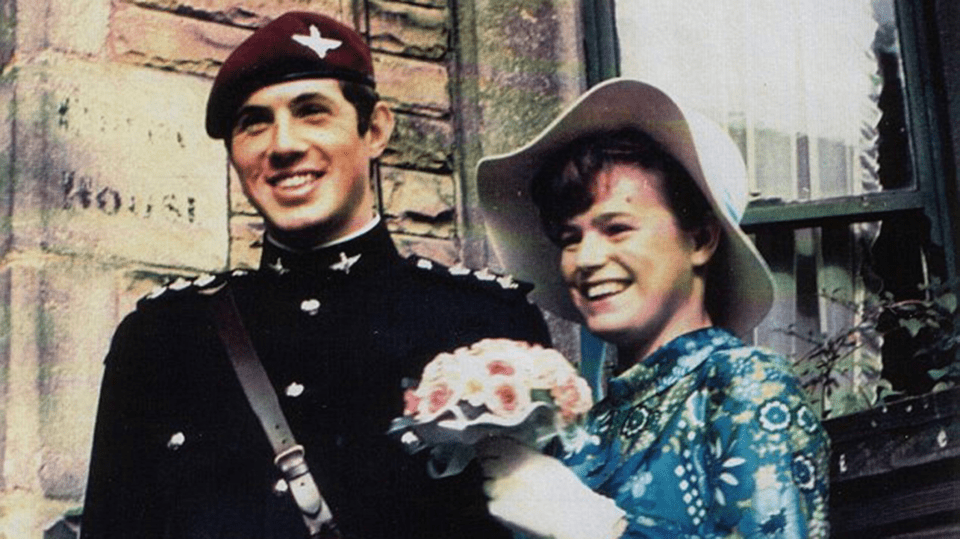

Clive had proudly worked as an army officer for many years and was highly respected. But he began to make mistakes in tasks he’d previously done with ease. He was issued several verbal warnings and one written warning over the quality of his work. He was also reported for being stubborn and difficult to manage. In 1992, after 23 years in the Army, Clive was made redundant.

The word ‘dementia’ wasn’t floated. After all, Clive was in his 40s. And people in their 40s couldn’t get dementia, right? Hindsight can be such a cruel thing. And though I wasn’t connecting the dots at the time, more signs emerged.

While in the process of applying for jobs, Clive decided he would embrace the role of ‘house husband’. I taught him a few basic recipes that he could follow, but even these proved too difficult. It wasn’t unusual for me to run into the kitchen at the smell of something burning – either the food or the utensil! We compromised on ready meals when it was Clive’s turn to cook.

Clive tried to take over the washing machine responsibilities but could never manage the various settings – and therefore he’d put everything on a hot wash. I learnt not to put my work clothes into the washing basket, knowing he would shrink them, and would instead wash them by hand when Clive was out of the house.

Whenever I read a bedtime story to the children, Clive would leave the room, finding an excuse not to read himself. I found this irritating and upsetting – I didn’t realise that he was probably unable to read easily by then. And I remember one day he brought me a bill that we needed to pay. It was for £102, and yet Clive had written a cheque for £1,002.

One of my scariest memories of that time was coming home from work to find a policeman on the doorstep, holding the hand of our three-year-old, Alan. Clive had taken our two children, both toddlers, to the swings and Alan, as he was occasionally prone to doing, had wandered off. Clive didn’t understand the seriousness of the situation and laughed it off. I, on the other hand, was devastated.

Stopping work wasn’t an option as I was the only one bringing in an income at this point. It was hard enough to make ends meet as it was.

Looking back, knowing what I do now, I lament not connecting all of these signs with dementia. But the truth is, things changed gradually, and I just adjusted to each new step. People do have conflicts with their boss. Husbands can forget they’ve promised to babysit. They have even been known to forget their wife’s birthday. And Clive never admitted he was having difficulties. In fact, he became very adept at hiding any problems.

I wish medical professionals had seen the signs of Clive’s dementia too. We could have enjoyed a few more years together without the constant anguish and uncertainty. It took five years from our first appointment with a GP to Clive finally receiving a diagnosis in 1994. He was 46 years old. I received a phone call and was informed that he had ‘pre-senile dementia’. Later, the diagnosis was modified to frontotemporal dementia.

Looking back, I rue many things about our experience. For one, the term ‘pre-senile dementia’ is full of stigma and I’m glad it isn’t used anymore. Secondly, when talking about Clive’s condition, the doctors only spoke to me, not him. Nobody told him about his diagnosis, what it meant, what to expect, or where to look for support. Deep down, I don’t think they knew how to talk to him, so they only spoke to me.

I was told that Clive’s dementia was an extreme outlier, that there wasn’t a cure and that there were some leaflets available if we wanted them. But we needed more than leaflets. I didn’t know a single person who had young onset dementia. For five years, all of Clive’s symptoms had been attributed to ‘life issues’. Was he drinking too much? Was he depressed? Were we having relationship problems?

In some ways, it’s heartening to look back on this time and realise how far we’ve come in recognising young onset dementia and supporting families it affects. In others, it fills me with sadness because we felt so alone. The expertise of a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse would have been life-changing at this point. The very first Admiral Nurse teams had just been established – but they were only in London, and we were in Oxfordshire.

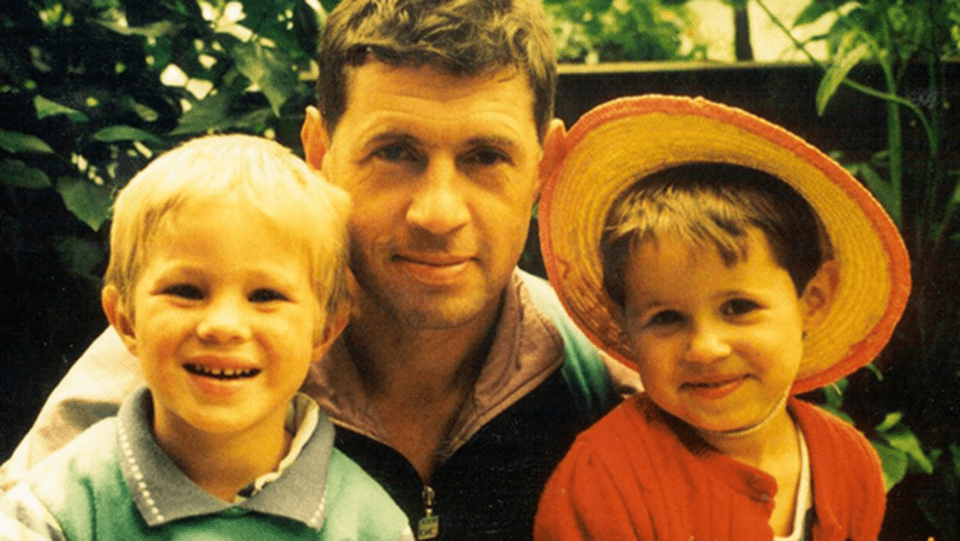

The next five years were difficult beyond words. At the time of Clive’s diagnosis, our children were three and four years old. Life became a juggling act between parenting, working full-time, and caring for Clive. We got by for a few years, but soon Clive’s needs were too great to manage at home and he had to go into full-time care. A year later, in 1999, he died. He was 51 years old.

Grief is such a complicated emotion. It lingers. It doesn’t operate on your terms. But in grief, I also realised that my own dementia journey hadn’t finished. I wanted to derive purpose from our painful experience. I owed it to Clive, and to every other person like him out there.

With the help of some incredibly dedicated people, I started The Clive Project, which sought to develop and provide a range of services for younger people with dementia and their carers in Oxfordshire. This grew to become YoungDementia UK and merged with Dementia UK in 2020.

In 2008, I also embarked on quite a drastic change of career. Both of my children had just finished school and moved away. And so, at the age of 58, I retired from my career as a computer programmer and moved to Manchester to take up a PhD exploring the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate brain changes in people with dementia. The underlying goal is to improve the rates of diagnosis. MRI scans hold so much potential in delivering a timely diagnosis. This is crucial not only now, but also in the future, if treatments become a reality, as early detection will be essential for these to work effectively.

For five years, Clive and I were bounced around medical appointments, with no real sense of what was happening, nor what was coming. I lost count of the number of tests we did, most of which were done with pencil and paper. I also lost count of the number of times Clive’s symptoms were attributed to ‘life factors’. With new technology comes great opportunity. And I have dedicated this new chapter of my life to making it a reality.

Purchase Helen’s book, ‘Losing Clive to young onset dementia’

Amy shares how she, her younger sister Chloe, and their dad Rob cared for her mum who was diagnosed with young onset frontotemporal dementia, aged 47.

When her partner Andy was diagnosed with dementia at the age of 52, Christine struggled to know where to turn. She is supporting our ‘We live dementia’ campaign to raise awareness of how our specialist dementia nurses can help.

Hannah’s husband Neil was diagnosed with young onset dementia at the age of 51. She shares how the whole family is living with dementia too.