Christine’s experiences of continence care

To coincide with the launch of the National Institute of Health Research’s report into continence, Christine Reddall speaks about the challenges she experienced in continence care after her late daughter Anna was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia in 2012.

When I was a nurse, continence care was one of those issues which people wanted to hide away from. I came across a lot of people who were buying their own continence products because they didn’t want to admit that there was a problem with themselves or the person they were caring for. It’s a very sensitive topic as some people believe it signifies a regression to childhood.

The importance of dignity

My daughter, Anna, was formally diagnosed at the age of 37 with BvFTD (behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia) in September 2012. As a family, we had started to notice ‘changes’ in Anna at the end of 2011. Although she didn’t have continence issues in the beginning, she did seem to have an obsession with the toilet. She would keep on locking herself in the toilet, banging on the walls and wailing. It was obvious sometimes that there was faecal matter on her hands. It was hard for us to know why she was doing this or what she was thinking.

I think this behaviour was just the beginning of her continence issues. If these behaviours had been picked up earlier, I believe it would have relieved a lot of our stress and would have spared her a lot of indignity.

Christine and Anna together before Anna’s diagnosis

Due to how quickly Anna’s dementia was progressing, it became too much of a challenge to support her at home. Eventually she had to go into a nursing home.

The obvious incontinence started towards the end of the second year in the nursing home. Urinary incontinence came before the faecal incontinence. There were times when she was visibly wet, or we could smell urine on her. Anna had lost the ability to know exactly what she was doing; how to wipe herself, where to put the paper, how to wash her hands. She was a wife, mum and a nurse, so cleanliness and hygiene were so important to her, but dementia had taken that away from her.

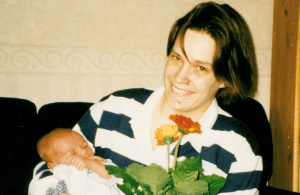

Anna with her first baby in 2001

Finding the right continence care

If she wasn’t closely supervised in the toilet, she would sometimes put her hands in her waste. This posed a huge hygiene risk, yet the carers were reluctant to supervise her as she was able to take herself to the toilet. She was a young woman who deserved her privacy. Also, Anna often refused to be helped as she could not acknowledge that she was having problems. She had anosognosia, a condition whereby the brain can’t recognise the illness, so the person affected has no perception of being ‘different’.

One of the biggest problems for Anna, and other people affected with dementia, is that badly managed incontinence can often lead to excoriated skin and urine infections which can then exacerbate the symptoms of dementia.

It was important for Anna’s dignity and everyone who visited her that she was clean and tidy. She loved to be cuddled by people so it was very necessary for her to be in dry clothes and smelling nice. The thought that she might not be clean when I wasn’t there was very distressing.

From the point of Anna’s diagnosis to her initial care review meetings, continence care was never mentioned. It just seems like continence care takes a backseat, especially for the younger person, and if professionals aren’t bringing it up, then families are less likely to either. If carers are not given information around how continence could become an issue, then it is hard for them to know how to address the problem and hard for them to be an effective advocate for their loved one.

We also need to understand that some people with dementia can only communicate that they have continence issues through their behaviour. This behaviour can sometimes be seen as disruptive, such as wondering, crying, banging. This often results in them being ‘told off’. It is up to the people who care to read these signs of distress and check if this behaviour is linked to a continence problem.

I had to use every ounce of my professional experience to get Anna the right support.

Finding continence products

I was lucky that I was a nurse and I knew about continence products and what was available. It must be so hard for people who don’t know how to go about getting help.

However, even with my experience, it was still a struggle to get the right continence products for Anna. I wanted to her to have the pull-up pants as they are more dignified and resemble normal pants, but she was only allowed five pairs of these a day as they are more expensive. Once these five were used, she had to wear the cheaper nappy style product. However, because she was so active and would roll around the floor, these would slip down or come undone. How undignified for her when you could see the obvious wet bulge.

Anna in her nursing home

Clothes were a big issue for her as well. It was difficult for us to find the right clothes that would accommodate the incontinence pads and make it easy for the nurses when they wanted to change her. Because of Anna’s rolling and crawling around the floor, we tried dungarees which helped a lot as they didn’t part in the middle. However, the care staff didn’t like them as it was fiddly to change her.

Menstruation

Though strictly not under the umbrella of incontinence, it must not be forgotten that the younger woman with dementia may still be menstruating. Anna was only in her 30s and was still having monthly periods. This was a massive source of distress for her. Normally able to manage her own stomach cramps and internal protection, she now did not understand what was happening to her. She needed help with using sanitary products and regular changing. Sadly, this common issue which affects women was dealt with by using nappy style products which must have been very uncomfortable and undignified. I have to admit that with everything else going on, I failed to acknowledge that she was still having periods. It was only when I eventually picked this up that she was prescribed medication to stop her from menstruating.

Christine and Anna on Anna’s 40th birthday

Improved continence care

It is often accepted by people caring for dementia patients that the elderly will develop continence issues. However, this does not apply as readily when caring for an individual living with young onset dementia. Anna’s carers told me how ‘strange’ they found it when Anna started to experience incontinence. Many of the carers were around Anna’s age and they felt quite embarrassed at having to wash and change her.

Whatever age, it is up to the professionals to discuss continence issues with the person with dementia, if appropriate, and with their family and carers. Even if the person is not having problems at the time, discussion still needs to take place for when the incontinence inevitably happens. Often, it is ‘expected’ that the older dementia person will suffer from incontinence. Dementia can take many forms and very often, the younger person can look ‘normal’ to others thus masking what is happening beneath the clothes.

If family members do mention incontinence, however subtle, then professionals need to be attuned to this and discuss it in more depth. If people are encouraged to talk openly and honestly about continence, support is easier to come by.

For any carer, try not to be embarrassed about continence; everybody goes to the toilet. It’s just that people with dementia cannot always recognise how or where they should toilet. It is not their fault, and they should always be treated with respect and dignity. When a younger person is diagnosed with dementia, some written information around how continence issues could surface later and ways to manage it would be extremely helpful.

Christine Reddall is the author of 2 books ‘Palliative Care for Care Homes’ and ‘Anna and the Beast. The true story of a young mum diagnosed with dementia aged 37’