Understanding dementia as a journey, not a final stop

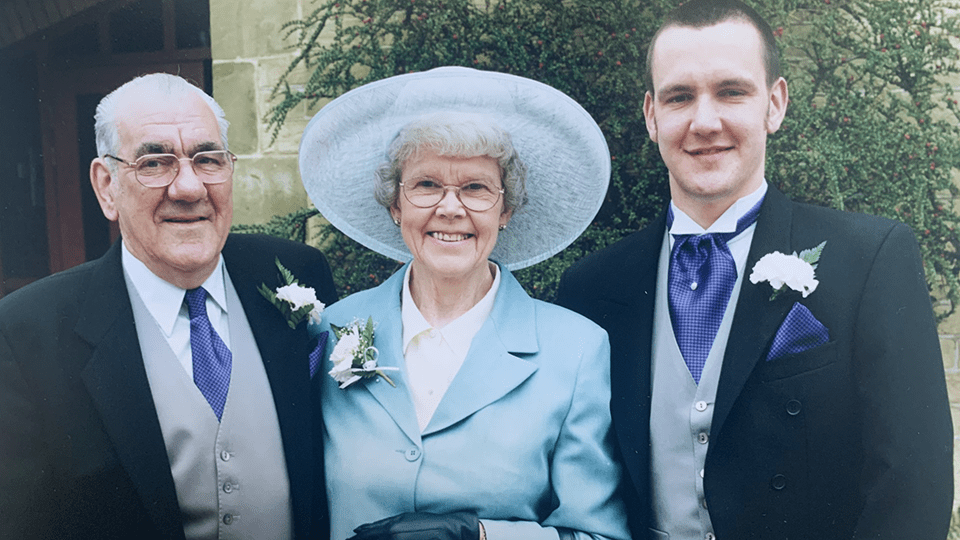

Andy opens up on how his approach to his dementia diagnosis has changed over time, and the two layers of stigma he has experienced.

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease. It is caused by reduced blood flow to the brain. It can cause problems with concentration, thinking and carrying out daily activities.

This guide, written by our specialist dementia nurses, explores the symptoms, causes and treatments of vascular dementia.

Vascular dementia is a form of dementia that occurs when the brain does not receive enough blood supply, meaning it cannot carry out its normal functions.

It is caused by damage or disease to the blood vessels in the brain, often as the result of a stroke or transient ischaemic attack(s) (TIAs), also known as ‘mini strokes’.

Vascular dementia can also result from other conditions that affect the supply of blood to the brain, such as high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes.

The main difference between vascular dementia and other types is that vascular dementia is caused by the brain not getting enough blood, whereas other common forms (eg Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body dementia) are caused by abnormal proteins building up in the brain.

The early symptoms of vascular dementia also differ from some other types – for example, changes in mood, behaviour and personality are initially more common than memory problems.

Blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the brain, and every aspect of human functioning depends on the brain having an adequate blood supply. When this is reduced, the nerve cells in the brain cannot communicate with each other and eventually die.

If the blood flow to the brain is interrupted by a sudden or gradual blockage or damage to blood vessels, it can lead to symptoms of vascular dementia.

While everyone will have their own experiences of vascular dementia, many people will share common symptoms.

The early signs of vascular dementia include:

If someone develops symptoms of dementia after a stroke, they may also have speech or vision problems.

About 10% of people with dementia have ‘mixed dementia’. This is a combination of two or more types of dementia – usually Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. The person may have symptoms of both forms of dementia.

In one specific type of vascular dementia, called subcortical vascular dementia or Binswanger’s disease, the early symptoms include loss of bladder control, speech problems, movement changes, falls and reduced facial expressions.

As vascular dementia progresses, daily living activities can become increasingly difficult, and people may struggle to look after themselves. In the later stages, common symptoms include:

As with other types of dementia, vascular dementia is progressive and is often roughly divided into three stages: early, middle and late.

In the early stage – which may last for months or even years – vascular dementia will begin to affect the person’s daily life, although the impact may not be severe at this point.

In the middle stages, the symptoms of vascular dementia will become more pronounced, and the person is likely to need increasing support with everyday life. There may be:

In the late stages of vascular dementia, every aspect of life is likely to be affected. The person is likely to need increasing levels of care, including support with eating and drinking, personal hygiene, communication and mobility.

Vascular dementia progresses at different rates for different people. The onset is often gradual, although in some cases – for example, if the person has a stroke – it may be sudden.

People with vascular dementia may have periods where their symptoms seem stable, followed periods where it progresses more rapidly or suddenly (sometimes referred to as ‘step-wise progression’). It is difficult, however, to predict when this might happen, so it is better to focus on what the person can do now and how you can support them, rather than on how quickly their condition might progress.

Vascular dementia is caused by narrowing, damage or disease to the blood vessels in the brain. There are various factors that can contribute to this. These include:

Like many other types of dementia, vascular dementia becomes more common as people get older. People over the age of 65 are more likely to get vascular dementia. However, it can also develop in younger people. When dementia symptoms develop before the age of 65, it is known as young onset dementia.

Men are slightly more likely to develop vascular dementia than women.

People from South Asian and African-Caribbean backgrounds are at increased risk of vascular dementia because they are more likely to have diabetes and cardiovascular conditions.

Vascular dementia is more common in people who have health conditions that can affect the supply of blood to the brain. These include:

Generally, vascular dementia is not thought to be hereditary. There is some evidence that people with a family history of vascular dementia have a slightly greater risk of developing the condition, but this is probably because diabetes, heart disease and strokes – which are associated with vascular dementia – can have a genetic link, rather than the condition being directly inherited.

Some people have a rare form of inherited vascular disease called CADASIL, which is linked to dementia. People with CADASIL are likely to have a family history of strokes. The symptoms typically begin between the ages of 30 and 50, and include repeated TIAs or strokes, migraine, slurred speech, weakness on one side of the body, confusion and memory problems. Around two out of three people with CADASIL will go on to develop dementia.

If CADASIL or another rare familial or genetic form of vascular dementia is suspected, the person’s GP or dementia specialist may refer them to a genetics service for counselling, advice and testing for the inherited gene.

Genetic forms of dementia are more common in people under the age of 65.

Some lifestyle factors may increase the risk of developing dementia:

An unhealthy diet that is high in calories, saturated fats (found in foods such as fatty meat like sausages and bacon, cheese, butter, ghee, cakes and biscuits, crisps, chocolate and pastries), processed foods (eg ready meals, cooked meat like ham, sweetened drinks), sugar and salt may contribute to vascular dementia.

This sort of diet is linked to health conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, which can lead to vascular dementia.

Drinking alcohol in excess can also cause health problems that could increase the risk of vascular dementia.

A lack of exercise can lead to problems like obesity, heart disease, high blood pressure and high cholesterol, which increase the risk of developing vascular dementia.

There is a strong link between vascular dementia and smoking. This is because it can cause blockages in the arteries, which can disrupt the blood flow to the brain. It can increase the risk of high cholesterol, high blood pressure, strokes and heart attacks.

While there is no guaranteed way to prevent vascular dementia, the best way to reduce the risk or delay its onset and progression is to follow the general advice for good heart health. This will help to prevent damage or disease to the blood vessels in your brain. This includes:

You may wish to ask your GP for certain health checks, such as a blood pressure check and blood tests for raised cholesterol, high blood sugar and any deficiencies or hormonal problems, to help detect abnormalities, which can then be treated and monitored.

Regular sight and hearing checks are also important to identify and treat any problems.

If someone is showing signs of dementia, it is important to get an accurate diagnosis so that advice, support and services can be put in place as soon as possible.

The first port of call is the person’s GP. To prepare for this appointment, it is helpful to keep a record of their symptoms, including:

If possible, a family member or someone else close to the person should accompany them to the appointment so they can share their observations.

At the initial appointment, the GP should ask the person about their symptoms and family medical history, and carry out some physical examinations (eg checking blood pressure, weight and heart rate) to rule out other conditions that may have similar symptoms to dementia, such as depression, stress, menopause and infections.

They should also order blood tests to check for possible underlying conditions like vitamin deficiency, thyroid problems, diabetes and high cholesterol.

The GP may conduct some brief cognitive tests, for example asking the person to name some common items, remember an address, and/or draw an everyday object (usually a clock face). However, as these initial tests usually focus on memory and orientation problems – which may not be significant in the early stages of vascular dementia – the person may score highly, which could delay a referral to a specialist.

If the GP suspects dementia, the person should be referred to a memory clinic for more comprehensive assessments focusing on attention, memory, fluency, language, visuospatial abilities and behaviour changes.

Because vascular dementia is caused by damage/disease in the blood vessels rather than a build-up of proteins in the brain, a brain scan alone will not identify if someone has vascular dementia.

However, a person who is suspected to have the condition should be referred for a brain scan such as an MRI or CAT scan by their GP or memory clinic. These scans may show evidence of stroke damage to the brain and may also help rule out other types of dementia (eg Alzheimer’s disease).

Currently, there are no specific treatments for vascular dementia, but there are some things that a person can do to manage its impact on their life and potentially slow its progression.

While there is no specific medication for vascular dementia, medications may be given for underlying conditions that could be contributing to or increasing the risk of dementia, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart problems or diabetes.

Medications for Alzheimer’s disease are not effective for vascular dementia unless the person has been diagnosed with mixed dementia (vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease).

If the person feels depressed or anxious about their diagnosis and the impact on their life, they should speak to their GP or specialist. In some cases, medication for depression or anxiety may be recommended.

A person with vascular dementia should be supported to:

These steps will not cure vascular dementia, but they may slow its progression.

For people in the early to middle stages of dementia, cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) may help with problems with thinking, memory, concentration and communication. This involves talking about their everyday interests, things relating to the current time and place, and past experiences and memories.

CST can take place one-to-one or in groups. You can find out if it is available in your area through the person’s GP or memory clinic.

People who are experiencing anxiety or depression connected to their vascular dementia may benefit from talking therapy like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which aims to change negative patterns of thought. The person can be referred for talking therapy by their GP or can refer themselves.

It is impossible to predict a person’s life expectancy after a diagnosis of vascular dementia. It will depend on factors such as their age, the stage at which they were diagnosed, and the impact of other conditions (it is not uncommon for people with vascular dementia to die of a heart attack or stroke before their dementia reaches an advanced stage).

Because everyone’s dementia progresses differently, it is better to concentrate on supporting the person to have the best possible quality of life now than to try to predict their life expectancy.

These tips may help to prevent and manage the effects of vascular dementia so the person with the diagnosis can live as well as possible.

Because everyone with dementia has their own unique experience, the support they receive should be tailored to their needs, based on your understanding of them as a person. However, these tips may help:

Andy opens up on how his approach to his dementia diagnosis has changed over time, and the two layers of stigma he has experienced.

Over the span of a decade, Chris cared for both parents with dementia. He shares his story to highlight the systemic flaws carers face.

As a carer for her mum, who has vascular dementia, Clare is taking part in our ‘We live with dementia’ campaign to make more people aware of the support our nurses offer.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about vascular dementia or any other aspect of dementia, please contact our free Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm; Saturday, Sunday and bank holidays 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December.

Alternatively, you can book a free, 45-minute phone or video appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

In most cases, vascular dementia is not inherited. People who have a family history of the condition may be more likely to develop it, but this is likely to be because conditions like heart disease, stroke and diabetes can run in families, rather than vascular dementia itself being inherited.

There is a rare form of vascular disease called CADASIL, which is inherited. Two in three people with CADASIL will go on to develop dementia. If you have any concerns about CADASIL or other genetic forms of dementia, please speak to your GP or specialist.

You may be able to reduce the risk of vascular dementia by ensuring you follow a healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet and regular exercise; stopping smoking; and not exceeding the recommended maximum weekly alcohol intake of 14 units.

However, some of the risk factors associated with vascular dementia cannot be changed – particularly age.

There is currently no cure for vascular dementia, but its progression may be slowed by making healthy lifestyle choices like eating a healthy diet, taking regular exercise, not smoking and drinking alcohol only in moderation.

In some cases, medication might be prescribed to manage underlying conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, but while these may slow down the progress of vascular dementia, medication is not a cure.

People with all forms of dementia may develop problems with eating and drinking. For example, they may forget to eat/forget if they have eaten, not recognise the signs of hunger, have difficulty preparing food, have changes in taste and appetite, or struggle to follow a particular diet (eg a diet for diabetes).

In the later stages of vascular dementia, problems with eating and drinking often increase – for example, the person may lose the ability to eat and drink independently, and have difficulties chewing and swallowing.

You might find our information on eating and drinking with dementia helpful.

If someone who drives is diagnosed with any form of dementia, they are legally required to tell the DVLA (DVA in Northern Ireland) and their vehicle insurer. This does not necessarily mean they will have to stop driving immediately (although this is a possibility), but they may need to take a driving assessment, or they may be issued with a shorter driving licence to renewed after one, three or five years. Please see our guide to driving and dementia for more information.

Mood changes are common in people with vascular dementia. The person may become more emotional with rapidly changing moods (‘labile mood’). This may include becoming agitated or angry at times.

Anger in people with dementia is often the result of confusion or distress. We have advice on helping to manage distressed behaviour.